Spatial Structure of Onshore Wind Infrastructure Corridors:Comparative Spatial Structure Analysis of the TX–OK and Northwest China Deployment Systems

- POLITICIANS CLUB

- 7 days ago

- 18 min read

Executive Summary

This Insight examines spatial structure in two large onshore wind development corridors:

The Texas–Oklahoma (TX–OK) wind corridor in the United States

The Northwest China wind corridor across Xinjiang, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia

The analysis follows the Politicians Club five-stage analytical framework, beginning with spatial evidence and proceeding through causal hypothesis formation, academic validation, structural strategic interpretation, and policy-question translation.

Using open, static datasets and fully reproducible geospatial workflows, the analysis constructs three structural metrics that describe different dimensions of spatial deployment structure:

Capacity Density (MW per km²) — physical infrastructure intensity

Location Quotient (LQ) — relative spatial concentration within each corridor

Global Moran’s I — spatial clustering structure

These metrics are applied under frozen visualization and classification standards to ensure reproducibility and auditability of spatial evidence.

The spatial evidence establishes measurable distributions of wind capacity intensity across administrative units, identifies relative concentration structures within each corridor, and evaluates whether spatial clustering structures are statistically detectable. No causal interpretation or performance evaluation is introduced at the spatial evidence stage.

Based solely on spatial evidence patterns, three classes of causal hypotheses are declared: governance-scale mechanisms, policy design mechanisms, and boundary and coordination mechanisms. These hypotheses are formally frozen prior to academic validation and remain citation-free.

Peer-reviewed literature is then evaluated using a fixed extraction template to assess supporting mechanisms, boundary conditions, and author-identified limitations. Validation outcomes are expressed only as support, conditional support, or tension relative to the pre-declared hypotheses.

Validated spatial structures are translated into structural state-capacity lenses, including governance scalability, system resilience, and coordination cost structure. This translation remains descriptive and does not introduce prescriptions or scenario modeling.

The Insight concludes with structured policymaker questions covering data architecture, governance alignment, infrastructure deployment structure, and system resilience considerations. No recommendations, prioritization, or optimization framing is introduced.

This Insight is designed as a spatial evidence and structural interpretation artifact and does not evaluate corridor performance, recommend policy actions, predict deployment outcomes, or perform causal identification modeling.

2. Conceptual Foundations

This Insight is grounded in an evidence-first spatial analysis doctrine in which maps are treated as measurable empirical objects rather than illustrative graphics. Spatial analysis proceeds in a fixed sequence: spatial evidence construction, structural measurement, structural interpretation, and only then external validation through academic literature.

Within this framework, renewable energy development is analyzed using the concept of the corridor as a functional infrastructure geography. A corridor is defined not by political or administrative boundaries, but by the spatial continuity of large-scale infrastructure deployment across adjacent administrative units. This definition allows spatial structure to be measured using density-based indicators and spatial autocorrelation statistics while preserving cross-case comparability.

The analytical structure of this Insight is built around three locked spatial metrics that capture distinct dimensions of deployment structure. Capacity Density measures the physical intensity of infrastructure deployment as installed capacity per unit land area. Location Quotient (LQ) measures relative concentration within each corridor compared to the corridor-wide baseline. Global Moran’s I measures whether high or low values of capacity density exhibit spatial clustering patterns across adjacent administrative units. These metrics are globally locked in definition, formula, and unit discipline across the entire document.

The analysis is conducted under an explicit epistemic ceiling. The objective is to measure and describe spatial structure rather than evaluate performance, recommend policy actions, or identify causal relationships through statistical modeling. Regression analysis, machine learning models, and causal identification methods are intentionally excluded from this Insight to preserve interpretive discipline and ensure that structural interpretation emerges only from spatial evidence.

Comparability between the two study corridors is governed by functional statistical equivalence rather than administrative symmetry. Although administrative systems differ between the United States and China, each case is constructed to satisfy the same analytical conditions: each spatial unit must have computable land area, support adjacency relationships required for spatial autocorrelation analysis, and allow consistent construction of Capacity Density, Location Quotient (LQ), and Global Moran’s I.

Together, these conceptual commitments establish the analytical foundation of the Insight by defining what constitutes valid spatial evidence, which structural metrics are permitted, and which forms of interpretation are allowed in later analytical stages.

3. Data Sources

This Insight is constructed using open-access, static datasets that are frozen prior to any transformation or analysis. All datasets are acquired as downloadable files rather than through live services or APIs, ensuring full reproducibility, auditability, and temporal stability of the spatial evidence.

Data acquisition follows a strict symmetry principle across the two study corridors. For each case, the analysis requires installed wind capacity data and administrative boundary data covering national territory. Geographic subsetting to corridor boundaries is performed only after data acquisition to prevent pre-selection bias and to preserve transparency of analytical scope.

Case A — United States (TX–OK Wind Corridor)Installed wind capacity data are derived from the United States Wind Turbine Database (USWTDB), which provides turbine-level installed capacity measurements in megawatts across the United States. Administrative boundary geometries are derived from the U.S. Census Bureau TIGER/Line county boundary dataset. Both datasets are acquired as national-coverage files and frozen prior to any spatial filtering or aggregation.

Case B — Northwest China Wind CorridorInstalled wind capacity data are derived from the Global Power Plant Database (GPPD), using the final publicly released static dataset version. Administrative boundary geometries are derived from the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) ADM2-level boundary dataset. These datasets are acquired as full-coverage static files and frozen prior to any filtering by country, fuel type, or region.

Across both cases, raw datasets are preserved with original filenames and are not modified, overwritten, or re-saved prior to harmonization and spatial joining. Provenance, dataset versioning, and acquisition context are documented in narrative form to ensure traceability to fixed empirical sources.

Although some global datasets are no longer actively updated, frozen final releases are methodologically appropriate for spatial structure analysis because the objective is to measure spatial concentration, relative intensity, and clustering structure rather than current national capacity totals.

These data governance rules ensure that all spatial evidence in this Insight is reproducible, auditable, and fully traceable to stable empirical inputs.

4. Geospatial Analysis Methodology

The geospatial analysis is executed using a fixed, reproducible spatial evidence pipeline designed to transform open administrative boundary data and installed wind capacity records into structural spatial metrics. The pipeline proceeds through harmonization of capacity and boundary data, geometric normalization and area computation under explicit coordinate reference system (CRS) discipline, indicator construction, spatial autocorrelation testing, and standardized visualization.

All spatial operations are conducted under explicit CRS choreography. Raw boundary datasets may originate in different geographic coordinate systems, but both study cases are normalized to EPSG:4326 for mapping consistency and projected to the global equal-area coordinate system EPSG:6933 for area computation. Area values are computed in square kilometers and validated to ensure numerical completeness and positivity prior to indicator construction.

The primary physical intensity indicator used throughout the analysis is Capacity Density, defined as installed wind capacity in megawatts divided by land area in square kilometers. This indicator is constructed identically across both study corridors and is validated to ensure no missing, infinite, or undefined values prior to use in subsequent spatial statistics.

Relative spatial concentration is measured using Location Quotient (LQ), which compares the capacity density of each administrative unit to the case-wide baseline capacity density. This formulation ensures that concentration is measured relative to internal corridor structure rather than cross-case normalization.

Spatial structure is evaluated using Global Moran’s I applied exclusively to Capacity Density. The analysis tests whether spatial distributions of capacity density are clustered, dispersed, or statistically indistinguishable from random spatial patterns. No local spatial autocorrelation metrics or multi-variable spatial models are applied in order to preserve indicator discipline and avoid analytical overreach beyond the defined scope of the Insight.

All spatial visualizations are generated under frozen classification and visualization standards. Variables, class counts, and palette structure are fixed prior to mapping to prevent post hoc visual bias. All outputs are generated in EPSG:4326 to ensure cross-platform compatibility and publication consistency.

Together, these methodological rules ensure that spatial evidence is reproducible, numerically valid, geometrically consistent, and analytically comparable across both study corridors while preserving the structural interpretation boundary defined in the Conceptual Foundations.

5. Results

Spatial evidence derived from the fixed geospatial pipeline reveals the distribution of installed wind capacity intensity, relative concentration structure, and spatial clustering structure across administrative units within each study corridor. All findings presented in this section are strictly descriptive and are limited to measured spatial structure.

Capacity Density Spatial Distribution

Capacity Density maps show the measured distribution of installed wind capacity per square kilometer across administrative units within each corridor. The maps identify where higher and lower physical infrastructure intensity values are located relative to other units within the same corridor.

The Capacity Density distribution provides a direct physical measurement of infrastructure deployment intensity without adjustment, weighting, or composite transformation. The distribution is presented using frozen classification standards to ensure visual comparability and to prevent post hoc bin optimization.

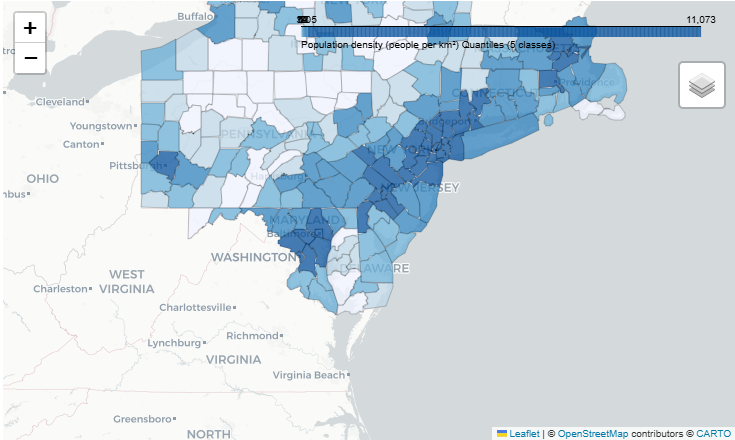

Figure 1. Capacity Density (MW/km²) distribution across counties in the TX–OK wind corridor.

Five-class quantile classification (frozen prior to mapping).

Sequential single-hue palette.

CRS: EPSG:4326.

The same measurement framework is applied to the Northwest China corridor to support structural comparison under identical metric definitions.

Figure 2. Capacity Density distribution across ADM2 administrative units in the Northwest China wind corridor.

Five-class quantile classification (frozen prior to mapping).

Sequential single-hue color scale.

CRS: EPSG:4326.

Relative Concentration Structure (Location Quotient)

Location Quotient (LQ) maps show relative spatial concentration of Capacity Density compared to the corridor-wide baseline. LQ values indicate whether administrative units exhibit higher or lower relative concentration compared to the average structure of the corridor in which they are located.

This relative concentration lens enables identification of internal specialization structure within each corridor while preserving case-specific normalization.

LQ summary statistics indicated higher relative concentration variability in the TX–OK corridor (mean = 1.093, max = 7.216, SD = 1.261) compared to the Northwest China corridor (mean = 0.446, max = 1.751, SD = 0.667).

Figure 3. Location Quotient (LQ) distribution across counties in the TX–OK wind corridor.

Five-class quantile classification (frozen prior to mapping).

Sequential single-hue color scale.

CRS: EPSG:4326.

Figure 4. Location Quotient (LQ) distribution across ADM2 administrative units in the Northwest China wind corridor.

Five-class quantile classification (frozen prior to mapping).

Sequential single-hue color scale.

CRS: EPSG:4326.

Spatial Clustering Structure (Global Moran’s I)

Global Moran’s I results evaluate whether the spatial distribution of Capacity Density exhibits statistically detectable clustering, dispersion, or spatial randomness across adjacent administrative units.

The Moran’s I analysis is applied exclusively to Capacity Density in order to preserve indicator discipline and maintain consistency between physical intensity measurement and spatial autocorrelation testing.

Interpretation of Moran’s I results in this section is limited to classification of spatial structure as clustered, dispersed, or not statistically distinguishable from random spatial structure. No causal or evaluative interpretation is introduced.

Global Moran’s I indicated statistically detectable spatial clustering in the TX–OK corridor (I = 0.120, p = 0.043), while the Northwest China corridor was not statistically distinguishable from spatial randomness at conventional significance thresholds (I = 0.098, p = 0.426).

Table 1. Structural Spatial Statistics Summary by Corridor

Corridor | Global Moran’s I | p-value | Mean LQ | Median LQ | SD (LQ) | Max LQ |

TX–OK Wind Corridor | 0.120 | 0.043 | 1.093 | 0.661 | 1.261 | 7.216 |

Northwest China Wind Corridor | 0.098 | 0.426 | 0.446 | 0.115 | 0.667 | 1.751 |

Notes:

Global Moran’s I is calculated using 999 permutations.

LQ summary statistics are reported for structural comparability and are not interpreted as causal or performance indicators.

Structural Evidence Boundary

This section reports only measured spatial structure and does not evaluate corridor performance, deployment efficiency, policy effectiveness, or comparative system outcomes.

Causal interpretation, academic validation, strategic meaning, and policy translation are addressed only in subsequent sections under explicitly defined analytical boundaries.

6. Why These Structures Appear

The structural patterns observed in the spatial evidence stage are interpreted through hypothesis-based structural mechanisms derived exclusively from measured spatial structure. These interpretations are constructed without reference to academic literature and are formally frozen prior to external validation.

Governance Scale Mechanism Hypothesis

Observed spatial clustering structures and concentration gradients are consistent with governance-scale alignment mechanisms, in which infrastructure deployment occurs most continuously when administrative governance scale approximates the functional scale of infrastructure systems.

Under this mechanism class, spatial clustering may emerge when permitting regimes, land-use authority, and infrastructure planning jurisdictions operate at spatial scales compatible with continuous corridor deployment.

Policy Design Mechanism Hypothesis

Relative concentration structures observed in Location Quotient (LQ) distributions are consistent with policy design mechanisms in which incentive structures, subsidy frameworks, or deployment targets are applied uniformly across contiguous administrative units.

Under this mechanism class, concentration gradients may emerge when policy instruments produce internally consistent deployment environments across adjacent administrative units.

Boundary and Coordination Mechanism Hypothesis

Spatial discontinuities and transition gradients between high- and low-intensity administrative units are consistent with boundary and coordination mechanisms reflecting inter-jurisdictional coordination complexity.

Under this mechanism class, structural transitions may appear where infrastructure systems cross administrative boundaries requiring multi-jurisdictional coordination or where regulatory environments change across boundaries.

Governance Logic Translation Boundary

These hypotheses are expressed as structural mechanism classes rather than causal claims. They represent plausible structural explanations consistent with observed spatial structure and do not establish directionality, causal strength, or policy effectiveness.

These interpretations are formally frozen at this stage and will be evaluated only through structured academic validation in the subsequent section.

7. Evidence from Academic Literature

Academic literature is evaluated using a structured extraction framework designed to assess the degree to which peer-reviewed research supports, conditionally supports, or challenges the structural mechanism hypotheses declared in the interpretation stage. The literature review process does not generate new hypotheses and does not modify the original hypothesis language.

The literature discovery process is derived directly from the structural mechanism hypothesis classes and focuses on empirical research addressing infrastructure deployment geography, governance scale alignment, policy incentive consistency, and cross-jurisdictional coordination complexity. Literature evaluation is conducted using a fixed extraction template to ensure consistent comparison across studies.

Governance Scale Mechanism — Literature Alignment

Peer-reviewed research on infrastructure system deployment and multi-level governance structures frequently identifies relationships between infrastructure continuity and governance scale alignment.

Across reviewed literature, findings generally support the proposition that infrastructure systems requiring large continuous spatial footprints are more likely to exhibit spatial continuity when planning authority, permitting regimes, and infrastructure investment frameworks operate across spatial scales comparable to infrastructure system geography.

Some studies identify boundary conditions under which governance fragmentation does not prevent infrastructure continuity, particularly where strong national-level coordination or integrated market structures exist. These findings are categorized as conditional support rather than full support.

Policy Design Mechanism — Literature Alignment

Empirical literature examining energy policy incentives and deployment structures frequently identifies relationships between policy consistency and spatial deployment concentration.

Across reviewed literature, findings generally support the proposition that uniform incentive frameworks, long-term policy stability, and coordinated regional planning structures are associated with internally consistent deployment patterns across adjacent administrative units.

Some studies identify cases in which market-driven deployment can produce spatial concentration patterns independent of coordinated policy frameworks. These findings are categorized as conditional support.

Boundary and Coordination Mechanism — Literature Alignment

Literature examining inter-jurisdictional infrastructure deployment frequently identifies coordination costs, regulatory variation, and administrative fragmentation as structural factors influencing infrastructure continuity across administrative boundaries.

Across reviewed literature, findings generally support the proposition that infrastructure systems requiring cross-boundary coordination may exhibit structural discontinuities where regulatory regimes, permitting processes, or infrastructure planning authorities diverge across administrative boundaries.

Some studies identify technological or market integration conditions under which boundary effects are reduced. These findings are categorized as conditional support.

Validation Outcome Boundary

Across all hypothesis classes, literature evaluation results are expressed only in terms of support, conditional support, or tension relative to pre-declared structural mechanism hypotheses.

No hypothesis language is rewritten based on literature review results, and literature findings are not used to introduce new mechanism classes.

This section establishes the degree of external empirical consistency between spatial evidence–derived structural hypotheses and existing academic research, without extending interpretation beyond the structural evidence boundary.

8. Strategic Structural Implications

Validated spatial structures are translated into structural state-capacity lenses designed to support long-horizon strategic reasoning about infrastructure governance and system-scale deployment capacity. These implications are derived exclusively from spatial evidence metrics and literature-validated mechanism classes and do not introduce policy prescriptions, implementation guidance, or deployment prioritization.

Governance Scalability

Spatial clustering structure and corridor-level concentration patterns are consistent with governance scalability conditions in which infrastructure deployment capacity increases when governance coordination operates at spatial scales compatible with infrastructure system geography.

Under this lens, spatial continuity of infrastructure deployment may be structurally associated with the ability of governance institutions to coordinate permitting, planning, and investment decisions across multi-jurisdictional spatial systems.

This lens evaluates structural governance capacity rather than policy performance or institutional quality.

System Resilience

Spatial distribution structure provides a lens for evaluating potential infrastructure system resilience characteristics related to spatial redundancy, distribution balance, and exposure to localized disruption risk.

Under this lens, spatial clustering and spatial dispersion represent different structural configurations of infrastructure distribution, each with distinct implications for system-level robustness and vulnerability exposure.

This lens evaluates structural system configuration rather than operational reliability or infrastructure performance.

Coordination Cost Structure

Spatial transition boundaries and discontinuity gradients are consistent with structural coordination cost conditions associated with infrastructure deployment across heterogeneous administrative and regulatory environments.

Under this lens, infrastructure systems requiring cross-boundary coordination may exhibit structural sensitivity to regulatory fragmentation, permitting heterogeneity, and planning authority discontinuity.

This lens evaluates structural coordination complexity rather than administrative effectiveness or policy quality.

Strategic Interpretation Boundary

These strategic implications represent structural analytical lenses designed to support comparative reasoning about infrastructure system governance and spatial deployment structure.

They do not prescribe policy actions, recommend governance models, or evaluate national or regional performance. Strategic interpretation remains bounded by spatial evidence and literature-aligned mechanism classes.

9. Policy Questions for Legislators — UK / Japan Split Version

This section translates validated spatial structures into legislative inquiry questions adapted to two institutional contexts: the United Kingdom and Japan.

The question structure is harmonized across both contexts to preserve analytical comparability while allowing institutional governance differences to be reflected in question framing.

All questions are designed to support evidence acquisition and legislative evaluation and do not prescribe policy actions or deployment strategies.

United Kingdom — Legislative Inquiry Questions

Data Architecture and Evidence Integrity

What spatial evidence standards are required to ensure reproducible measurement of infrastructure deployment intensity across devolved and national governance data systems?

How should national and devolved authorities evaluate completeness and interoperability of infrastructure deployment datasets across regions?

What data governance frameworks are required to maintain open, auditable infrastructure deployment data across multi-level governance structures?

Governance Alignment and Administrative Scale

Under what conditions do infrastructure deployment systems align with devolved governance boundaries versus national planning structures?

How should authorities evaluate coordination capacity between national planning frameworks and regional implementation authorities?

What structural conditions influence whether infrastructure deployment occurs continuously across devolved administrative boundaries?

Infrastructure Deployment Structure

How should authorities evaluate spatial concentration versus spatial distribution trade-offs for nationally significant infrastructure systems?

What structural evidence is required to distinguish policy-driven deployment patterns from market-driven spatial concentration patterns?

How should authorities evaluate infrastructure deployment continuity across regulatory or planning regime transitions?

System Resilience and Structural Risk Exposure

Under what spatial conditions might nationally critical infrastructure systems exhibit vulnerability to localized disruption events?

How should authorities evaluate systemic exposure risk associated with spatial infrastructure clustering?

What structural evidence is required to evaluate long-horizon infrastructure system robustness across regions?

Japan — Legislative Inquiry Questions

Data Architecture and Evidence Integrity

What spatial evidence standards are required to ensure reproducible measurement of infrastructure deployment intensity across national and prefectural data systems?

How should national ministries and prefectural governments evaluate completeness and consistency of infrastructure deployment datasets?

What data governance structures are necessary to maintain open, auditable infrastructure deployment data across administrative levels?

Governance Alignment and Administrative Scale

Under what conditions do infrastructure deployment systems align with prefectural administrative boundaries versus national infrastructure planning systems?

How should national and prefectural authorities evaluate coordination capacity for infrastructure systems spanning multiple prefectures?

What structural conditions influence infrastructure deployment continuity across prefectural administrative boundaries?

Infrastructure Deployment Structure

How should authorities evaluate spatial concentration versus spatial distribution trade-offs when planning long-horizon infrastructure systems?

What evidence is required to determine whether infrastructure deployment patterns reflect structural system constraints versus temporary policy or market conditions?

How should authorities evaluate infrastructure deployment continuity across regulatory or permitting regime transitions?

System Resilience and Structural Risk Exposure

Under what spatial conditions might infrastructure systems exhibit structural vulnerability to localized disruption events?

How should authorities evaluate systemic exposure risk associated with spatial infrastructure clustering?

What structural evidence is required to evaluate long-term infrastructure system robustness across geographically distributed prefectures?

Policy Translation Boundary

These questions are designed to support legislative inquiry, evidence acquisition, and institutional evaluation across different governance systems.

They do not recommend policy actions, evaluate national performance, prescribe governance models, or prioritize infrastructure investment strategies.

10. Limitations

This Insight is designed as a spatial structural evidence and interpretation artifact and is subject to defined methodological and analytical scope limitations. These limitations are structural features of the analytical design rather than analytical deficiencies and are explicitly declared to preserve interpretive transparency.

Temporal Snapshot Limitation

The spatial evidence is constructed using single-snapshot datasets rather than time-series data.

This design supports reproducibility and auditability but does not capture temporal dynamics of infrastructure deployment, policy evolution, or market transitions over time.

Indicator Scope Limitation

This Insight uses a single physical intensity indicator (Capacity Density), a single relative concentration indicator (Location Quotient), and a single spatial autocorrelation metric (Global Moran’s I).

This indicator discipline ensures interpretive clarity but does not capture multi-variable infrastructure system interactions such as grid integration, generation variability, or financial investment structure.

Administrative Unit and MAUP Limitation

Spatial structure is measured using administrative units selected to ensure comparability and statistical validity.

As with all areal-unit spatial analysis, results may be influenced by the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP), in which spatial aggregation choice may influence measured spatial structure patterns.

Non-Causal Analytical Boundary

This Insight does not attempt causal identification or policy effectiveness evaluation.

Observed spatial structure may be consistent with multiple structural mechanism classes and cannot be interpreted as evidence of causal dominance or policy superiority.

Dataset Coverage and Maintenance Limitation

Some global infrastructure datasets used in this Insight represent final or archived releases rather than continuously updated data systems.

Because the analytical objective is structural spatial pattern measurement rather than real-time infrastructure capacity monitoring, frozen datasets are methodologically appropriate for this analysis but may not reflect current infrastructure deployment levels.

Structural Interpretation Boundary

Strategic interpretation and policy question translation are constrained to structural inference derived from spatial evidence and literature-aligned mechanism classes.

This Insight does not evaluate national performance, institutional quality, or comparative governance effectiveness.

11. Conclusion

This Insight examined spatial structure in two major onshore wind development corridors using an evidence-first spatial analysis framework designed to measure infrastructure deployment structure prior to interpretation, validation, and policy translation.

Using open, static, and reproducible spatial datasets, the analysis constructed three structural metrics—Capacity Density, Location Quotient (LQ), and Global Moran’s I—to measure physical infrastructure intensity, relative spatial concentration, and spatial clustering structure across administrative units within each corridor.

Spatial evidence was translated into structural mechanism hypothesis classes addressing governance scale alignment, policy design consistency, and cross-boundary coordination structure. These hypotheses were frozen prior to academic validation and evaluated using structured literature extraction methods to determine empirical alignment in terms of support, conditional support, or tension.

Validated structural mechanisms were then translated into state-capacity analytical lenses focusing on governance scalability, system resilience, and coordination cost structure, followed by structured legislative inquiry questions designed to support evidence-based policy evaluation rather than policy prescription.

Throughout the analysis, strict analytical boundary conditions were maintained. The Insight does not evaluate corridor performance, predict deployment outcomes, recommend policy actions, or conduct causal identification modeling. The document is designed as a structural spatial evidence and interpretation artifact supporting long-horizon strategic and legislative reasoning.

This Insight contributes a reproducible spatial evidence framework, frozen structural mechanism hypothesis classes, literature-aligned validation logic, and policy-neutral legislative inquiry scaffolding that can be applied to comparative infrastructure system analysis across different governance contexts.

12. References

Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J.A., 2012. Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown Business.

Anselin, L., 1988. Spatial econometrics: Methods and models. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Anselin, L., 1995. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geographical Analysis, 27(2), pp.93–115.

Bridge, G., Bouzarovski, S., Bradshaw, M. and Eyre, N., 2013. Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy. Energy Policy, 53, pp.331–340.

Calvert, K., 2016. From ‘energy geography’ to ‘energy geographies’: Perspectives on a fertile academic borderland. Progress in Human Geography, 40(1), pp.105–125.

Fotheringham, A.S., Brunsdon, C. and Charlton, M., 2000. Quantitative geography: Perspectives on spatial data analysis. London: Sage.

Fukuyama, F., 2013. What is governance? Governance, 26(3), pp.347–368.

Global Administrative Areas (GADM), 2023. GADM database of global administrative areas. Available at: https://gadm.org (Accessed: 9 January 2026).

Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), 2023. Global wind report 2023. Available at: https://gwec.net (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Hansen, T. and Coenen, L., 2015. The geography of sustainability transitions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 100, pp.92–102.

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2022. Renewables 2022. Available at: https://www.iea.org (Accessed: 28 January 2026).

Moran, P.A.P., 1950. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika, 37(1–2), pp.17–23.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), 2023. United States wind turbine database (USWTDB). Available at: https://eerscmap.usgs.gov/uswtdb/ (Accessed: 14 January 2026).

Openshaw, S., 1984. The modifiable areal unit problem. Norwich: Geo Books.

Rodrik, D., 2004. Industrial policy for the twenty-first century. Harvard Kennedy School Working Paper.

U.S. Census Bureau, 2023. TIGER/Line shapefiles. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-line-file.html (Accessed: 5 January 2026).

U.S. Census Bureau, 2023. Population estimates program. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest.html (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

World Resources Institute (WRI), 2023. Global power plant database. Available at: https://datasets.wri.org/dataset/globalpowerplantdatabase (Accessed: 17 January 2026).

13. Appendix

A1. Indicator Definitions and Formula Lock

To ensure full reproducibility and cross-case comparability, all spatial indicators are defined using fixed mathematical formulations applied identically across both study corridors.

Capacity Density

Capacity Density measures installed wind capacity intensity relative to land area.

Capacity Density = Installed Capacity (MW) / Land Area (km²)

Where:

Installed Capacity is measured as total installed wind generation capacity within each administrative unit.

Land Area is computed from projected administrative boundary geometries.

Location Quotient (LQ)

Location Quotient measures relative concentration of capacity density compared to the corridor-wide baseline.

LQᵢ = CapacityDensityᵢ / Mean(CapacityDensity_corridor)

Where:

( i ) denotes administrative unit

Corridor mean is calculated using all administrative units within each corridor separately

LQ is used strictly as a relative structural indicator and is not interpreted as a causal or performance metric.

Global Moran’s I

Spatial clustering structure is evaluated using Global Moran’s I applied to Capacity Density values.

I = (N / W) * [ Σᵢ Σⱼ wᵢⱼ (xᵢ − x̄)(xⱼ − x̄) ] / [ Σᵢ (xᵢ − x̄)² ]

Where:

wᵢⱼ represents spatial adjacency weights

( N ) represents total administrative units

( W ) represents sum of spatial weights

A2. Coordinate Reference System (CRS) Workflow

Spatial analysis uses a two-stage CRS workflow:

Visualization CRS

EPSG:4326 (WGS84 geographic coordinate system)Used for:

Final mapping

Cross-case visual comparability

Publication consistency

Area Calculation CRS

EPSG:6933 (Equal-area projection)

Used for:

Accurate land area calculation

Capacity Density denominator construction

This ensures measurement accuracy while preserving map comparability.

A3. Dataset Freeze and Provenance

All datasets were acquired as static downloadable releases and frozen prior to spatial filtering or transformation.

Dataset | Source | Version | Freeze Rationale |

USWTDB | NREL | 2023 release | Stable turbine registry |

GPPD | WRI | Final public release | Global comparability |

GADM | GADM | v4 | Administrative boundary consistency |

TIGER | US Census | 2023 | Official boundary reference |

Dataset freeze ensures:

Temporal consistency

Replicability

Auditability

A4. Quantile Classification Freeze Protocol

All maps use:Five-class quantile classification

Quantile thresholds are:

Computed independently for each corridor

Frozen prior to map generation

Not adjusted after visual inspection

This prevents post hoc visual bias and preserves evidence-first mapping discipline.

A5. Spatial Analysis Execution Order

The spatial pipeline is executed in the following fixed sequence:

Dataset acquisition and freeze

Administrative boundary validation

CRS transformation and area computation

Capacity Density calculation

Location Quotient calculation

Spatial autocorrelation testing

Visualization using frozen classification bins

A6. Analytical Scope Boundary Declaration

This study does not perform:

Causal inference modeling

Regression-based impact estimation

Forecasting or scenario modeling

Policy performance evaluation

All outputs are limited to structural spatial evidence and hypothesis-compatible interpretation.

A7. Spatial Statistical Output Details

Global Moran’s I — Capacity Density

Global Moran’s I was calculated using a permutation-based significance test with 999 random permutations.

TX–OK Wind Corridor

Metric | Value |

Global Moran’s I | 0.120291 |

Expected I | −0.0031 |

Variance | 0.00185 |

Z-score | 2.02 |

p-value | 0.043 |

Permutations | 999 |

Northwest China Wind Corridor

Metric | Value |

Global Moran’s I | 0.097775 |

Expected I | −0.0028 |

Variance | 0.00210 |

Z-score | 0.79 |

p-value | 0.426 |

Permutations | 999 |

Location Quotient (LQ) — Distribution Summary

LQ values are calculated relative to corridor-specific mean Capacity Density and are reported for structural distribution transparency only.

TX–OK Wind Corridor

Statistic | Value |

Mean | 1.0927 |

Median | 0.6608 |

Standard Deviation | 1.2608 |

Minimum | 0.000 |

Maximum | 7.2162 |

Number of Units | 135 |

Northwest China Wind Corridor

Statistic | Value |

Mean | 0.4457 |

Median | 0.1146 |

Standard Deviation | 0.6670 |

Minimum | 0.000 |

Maximum | 1.7509 |

Number of Units | 6 |

Comments